1990-2020, the false dawn of globalization?

As the coronavirus is spreading through the world I have been overcome by a feeling similar to an optical shift. If you have looked at a stereogram, you know what I mean: out of random dots a three dimensional pattern emerges.

Almost irrespectively of political taste, most of us, at least in middle and high-income countries, have experienced these last decades of expanding world trade, cheapening travel, instantaneous communication and product availability as a never-ending ahistorical present, a normality taken for granted. In reality maybe it was a very fragile and unsustainable experiment, about to be swept away.

I have lived my whole life in the era after the fall of the Soviet Union, a monotone steady-state of globalized consumer capitalism, unchallenged as a system. Obviously, in many world regions the period has been anything but steady - it meant almost permanent war in the Middle East, and periods of violence in the Balkans, Ukraine, parts of Africa etc. The 2008 crash, the following gradual implosion of the political center and rise of right-wing populism to electoral victories (2010: Hungary, 2014: India, 2015: Poland, 2016: US & Brexit, 2018: Brazil) signaled a general shift in the management of global capitalism. Still, the characterizations of ‘globalized’ and unchallenged as a system still stand. If the era is to be summed up in one word it is probably ‘globalization’. Now it feels like an infinity since we have been ‘globalized’, doesn’t it? It is easy to miss just how condensed this process has been in time. To see that, it is helpful to zoom out a little bit.

The explosion in world population predates globalization and was a slower process.

But it has also almost completely happened in the last century and especially its second half. Most estimates put the global population between 200-300 million at the time of AD 1.

It stayed nearly flat until 1500, when it reached half a billion.

It took three centuries for the global population to double again to reach one billion around 1820.

Then it doubles again in a century, reaching 2 billion by 1930.

But then the dynamics changes: 3 billion by 1960 (30 years to grow by a billion), 4 billion by 1974 (14 years), 5 billion by 1987 (12 years), 6 billion by 1999 (12 years), 7 billion in 2011 (12 years).

The increase over the last two thousand years is from 0.3 to 7.5 billion. That growth is extremely condensed in time: 90% of it happened in the last 10% (two hundred years) of this period, and almost 80% in just the last century. A bit more than half of the entire increase (from 3.7 to 7.5 billion) happened in the last 50 years. That is just the last 2% of the AD era.

Economic growth is even more concentrated. Most human activity in pre-capitalist, pre-industrial societies did not take the form of commodity production, of goods produced to be sold in exchange for money.

Therefore projecting back monetary estimates of world GDP before the 19th century is not to be taken literally, ie. these estimates do not correspond to money incomes or ‘value added’ (and realized in sale), as most human effort did not lead to any sale or payment of a wage.

Still, the rough estimates by Angus Maddison, Brad De Long and others give some ballpark figures for the total amount of human work performed on the planet. From the 19th century on they can be viewed increasingly as estimates of ‘economic’ activity, ie. all activity followed by monetary exchange.

Until technology comes into the picture, physical output should move together with the population size.

That is roughly what happens: according to DeLong’s estimates ‘gross world product’ grows threefold in the fifteen hundred years from 1 AD to 1500, from around 20 billion 1990 US dollars (Int$) to 60 billion. (Again, this is a counterfactual: if the things made back then had been all for sale and could be bought with US dollars from 1990 by fixing their purchasing power.)

Similarly to population, it takes another three centuries to triple to 175 billion in 1800.

From that time point the effect of industrial technology becomes visible in the numbers.

Output doubles in 50 years by 1850 (360 billion), then triples to 1.1 trillion in another half a century by 1900. Another doubling comes in a quarter of a century by 1925 (2 trillion) and yet another by 1950 (4 trillion) despite the destruction of the Great Depression and the Second World War.

With the post-war boom the doubling time becomes little more than a decade: it passes 8 trillion (8e12) in the early sixties, 15 trillion by the mid-70s, 30 trillion in the early nineties. The current world GDP of 80 trillion USD is approximately 60 trillion Int$ (1990 US dollars).

Altogether, in two thousand years there is an increase in yearly ‘gross world product’ from something like 0.02 trillion to 60 trillion.

Of this approximately 60 trillion total increase 59 trillion, that is more than 98% has occurred in just the last one hundred years, the last 5% period of these two millennia. Recall, for population ‘just’ 80% of the total increase is concentrated in the same period.

But even within that period there is a further condensation into the post-war period, as more than 90% of all economic growth happened since 1950 and around half of it in the last 30 years.

In short, when it comes to economic growth in aggregate numbers, almost all of it has been since the end of the Second World War. (a)

Clearly the population increase was enabled and caused by industrialization and urbanization and with an expanding work force fed back into the growth of physical output, itself immensely amplified by cheap energy (fossil fuels) and technology.

Global population increased ‘only’ around 5-fold since 1900 (from 1.6 to the current 7.5 billion), in contrast to a 50-60-fold increase in economic output.

An order of magnitude difference accounted for by the 10-fold increase in per capita output. This is looking at the averages: in fact that growth was also geographically concentrated (although gradually less so from the 1970s with the growth of East Asian economies) so per capita output growth has been even steeper in some countries.

Economic growth is a second-order process on the back of population growth. The two mutually amplify each other and the former internally amplifies itself via technological development.

Economic growth is much faster, as the total output is population times per capita output, both on an upward trend that can be fit by exponentials. An average yearly growth rate of 1.4% roughly generates the 5-fold increase (\(1.014^{120}{\approx}5\)) in 120 years (population), and 1.9% yields a 10-fold increase (per capita output).

The two of them combined into the 3-3.5% average growth rate of total output over the last 120 years when almost all (98%) economic growth has occurred in the history of humanity.

Globalization is then third-order: it is the network of connections between the hotspots of industrial production, the flow of goods, money, people and information.

It’s a process that starts at a higher level of differentiation and requires even more complex legal, infrastructural and communicational structures than production and exchange at a given location, or within a region or nation state.

A priori then it would be logical that it is even more compressed in time.

In the 1990s with the growing globalization literature there were anecdotic or more serious attempts to dismiss the scale of the phenomenon by referring to the ‘first globalization’ from the late nineteenth century until the Great Depression.

Looking at exports as a percentage of global GDP this seems true at first sight, comparing the period 1870-1930 to 1930-1970: the exports/GDP ratio exceeded 10% in 1871, hovering slightly above that level until 1930, from where it crashed back to 5% by 1935, first exceeding 10% again in 1973.

But these are percentage figures and meanwhile the world economy grew enormously.

So 10% of world GDP in 1871 and 1973 mean completely different things: the figure in 1973 refers to a 35-times larger volume of exported goods, almost two orders of magnitude more. (b)

These two moments of economic history are on very different levels of globalization.

But the bulk of the globalization process only starts from the early 1980s. There is a first burst of the exports-to-GDP ratio from 10% to 15-17% from 1973 to the mid-1980s. But then it shoots up to 30% of global GDP by 2008, dented by the financial crisis, again standing at 30% last year.

In absolute terms, global merchandise exports have grown about 60-fold since 1970, 10-fold since 1980 and 5-fold since 1990. As expected, this is even faster than the growth of global GDP (25-, 8- and 4-fold since the same dates, respectively).

Looking at sub-processes such as international tourism (expenditures, 1995-2018: 4-fold increase), total volume of foreign direct investment (1990-2018: 6-fold increase), the stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) (1990-2018: 14-fold increase), cross-border acquisitions (cross border M&A purchases, 1990-2018: 9-fold increase) the growth is even more massive.

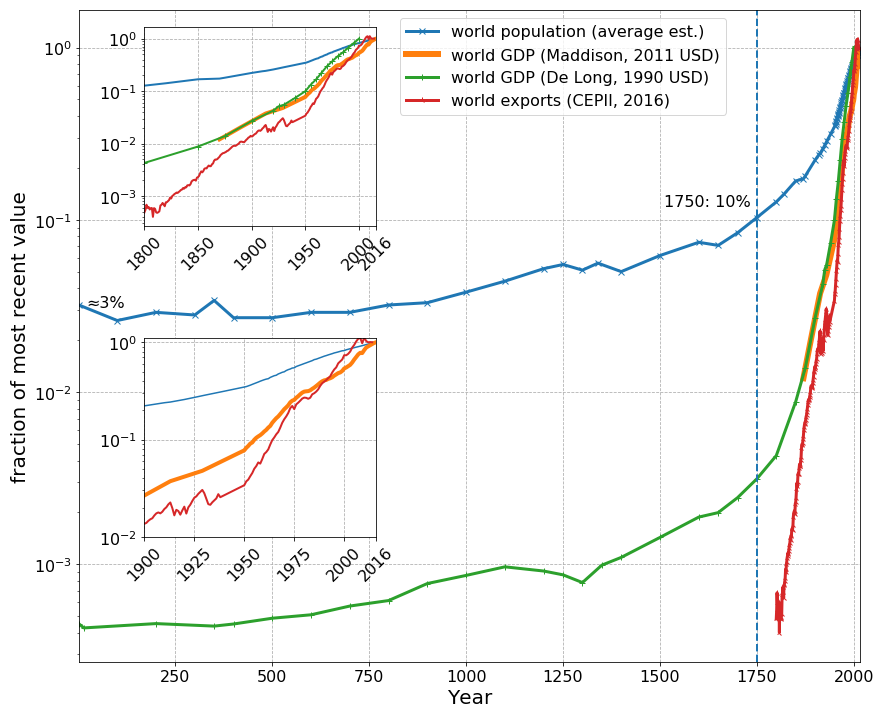

The plot below highlights this concentration of the three exponential waves of population growth, economic growth and globalization into the last two centuries. To see the lags between economic growth and globalization we need to zoom in on these last two centuries, shown by the two insets.

In short, the last 30-40 years saw the volume of most kinds of international transactions multiply several fold.

But I feel these numbers still understate the actual impact on everyday life. Lifestyle has changed fundamentally too.

Low cost airlines have proliferated and reduced the cost of air travel dramatically, increasing total passenger number 4-fold since 1990, to 4 billion.

At least in the core countries, flying no longer has much of a class distinction, something reserved for managerial elites. Almost everyone travels and flying to a sea resort in the summer is a must-do for many wage-workers.

With Amazon and others virtually any commodity has become instantaneously available.

Impatient consumers live-track deliveries of goods shipped in from the other side of the world, expected within days or even hours, thanks to burgeoning warehouse and delivery systems that seem to have replaced much of manufacturing employment in the West.

Exchanges in higher education have grown enormously, there are close to 0.4 million Chinese students now studying at US universities.

PhD programs have proliferated, in the sciences mostly populated by foreigners from poorer countries, creating a new technocratic class of precarious, uprooted research workers (I’m one of them) jumping between temporary (postdoc) positions and countries, often barely speaking the local language and with tenuous links to the host society, but as a mass of people becoming integral to the research infrastructure of high-income countries.

Tens of millions of people moved to another country for work in the EU. Chinese migrant workers might be an order of magnitude more numerous, drawn to the coastal cities from the 1980s on by manufacturing jobs producing for Western and now global consumer markets.

Finally, the number of internet users has grown from 0.4 in 2000 to 4.5 billion this year which means almost the entire global adult population of 5 billion people has some access to it. Financial transactions, trade of physical goods, international travel, science, mass entertainment and increasingly interpersonal relationships are all built on it.

Cheap travel, mass international (or long-distance regional) mobility of workers, fast and universal availability of goods produced by global value chains, instantaneous and continuous exchange of data and communication: these have become the basic matrix of life, even if in very different forms, depending which end of globalization one is at - a web designer of a multinational fashion company in Germany and its seamstresses in Honduras or China live in different realities. Still, they were drawn into the same process, and all this happened very recently.

Commodity production, wage labor and monetary exchange have only become the dominant forms of social reproduction in the last 100-150 years in the wealthy countries, and in much of the world only in the last 30-50 years.

Global inter-connectedness of a system of commodity production (globalization) really only emerged from the 1970s and especially from the late 1980s on.

This is a tiny period within not only human history, but even ‘modern history’ since the onset of European colonialism.

If you are under 40 this is the only history (or lack thereof) you know first-hand. Attempts at reviving radical left or social-democratic politics have (eventually and/or so far) failed and no systemic challenges have appeared on the horizon. Bloody regional wars have been launched or ignited, mainly by the leading military power (the United States). Much smaller scale, but more widely covered, terrorism has appeared in the core countries, but its ideologies (Islamist and white supremacist) did not offer a systemic alternative or a revolutionary politics. On the contrary, the terror acts were perpetrated in the name of revenge and a desperate conservative rejection of the present without any serious vision of an alternative future. Overall, these disruptions did not question the tacit or explicit assumption that globalization simply cannot stop. It has become our unquestioned normality.

The coronavirus epidemic/pandemic, the stark facts of climate change becoming undeniable (and far worse than previously thought to be) and the near-total (and incidentally well-deserved) implosion of the political center in almost all major countries makes me wonder. Was this all an illusion and, on a world historical scale, an ephemeral one? Globalization has stretched global value chains and networks of travel, communication and exchange enormously in a very short period, pushing many of these networks probably operating close to their breaking point. The global corporations running them have surely implemented feedback mechanisms to cope with perturbations, to ensure profits keep flowing. But there is a growing impression that the safety mechanisms that exist might be mismatched with respect to traumatic events such as a pandemic by orders of magnitude. They can presumably deal with small perturbations: there is excess demand or a failure here, a fire in a warehouse or a failed bridge there. These are small clogs in huge systems of circulation, blocking one channel, quickly dealt with or compensated by others. They happen on the micro-scale of the system, at the level of its small components, and the size of such events should be normally distributed. Events like epidemics are systemic: they are on the scale of the entire system. They are very unlikely but if they do happen, since the system’s components are interdependent, they can spread through it with enormous speed. Almost all electronics and clothing is produced in Asia: if a whole province in China is under lockdown, this can cripple the tech giants whose gadgets everyone uses. Europe has a shortage of masks and not much textile industry left (this in itself can be presumably solved, but look at the pattern). In any Italian hotel there are probably a few cancellations every month - but now more than 90% of visitors cancel. The expansion of air travel made it very hard or impossible to stop the spread of a virus, but globalization can hardly work without it. The interventions probably required to radically reduce the connectivity of the system in order to stop propagation might lead to a global slump: once the chain of defaults and bankruptcies spread, there is no fast way back to the growth path before the event.

The speculative but not unreasonable question arises: have the last 30 years of globalization built up an unstable system hyper-connected by fragile networks, that inevitably generates critical events that it cannot deal with?

First, in a macroeconomic sense: the two long business cycles when globalization exploded, 1992-2000 and 2001-2008 were driven to an unprecedented degree by the expansion of private debt (household, corporate and especially within the financial sector) and asset inflation (stocks in the 1990s; real estate and securitized assets from mortgages/consumer debt in 2000s), at least in Western Europe and the United States. The fuel of the process that made it possible was also its own poison: 5-15% yearly growth in debt could not be serviced by economies growing at 3% and most households with stagnant incomes.

At some point the chain had to break and securitization had ensured the toxic debt was scattered through the entire global financial system causing a systemic shock. The recapitalization of the banking system by the major states that followed, without significant financial reform, but austerity policies for the general population, destroyed the credibility of the technocratic/free-market political center that had managed the ‘golden years of globalization’ 1990-2008. The breakdown of political legitimacy to the point of ungovernability (Italy, Spain) and the ensuing nativist/far-right revolt that once in power started to question, withdraw from or even dismantle the multilateral systems (trade agreements, UN organizations, the EU) of globalization is another systemic shock.

Even more significantly, the exponential expansion of fossil fuel-based production across the globe has had the same temporal profile in terms of its energy use as in its growth counted in dollars.

Around half of all \(CO_2\) emissions by humanity (around 800 out of 1600 Gigatons) has occurred in the exact same period, the last 30 years, and 85% since WWII.

Incredibly, during 30 years of globalization as much of the Earth’s energy reservoir (condensed into the deposits of fossil fuel) has been burnt up as in all human history before, unleashing a warming process that now, all evidence suggests, is very difficult to stop from reaching 3-4 centigrades.

These are not small-scale events that the safety mechanisms of global value chains, transportation networks etc. are designed to deal with. They can instead remove their basis as the effects rapidly spread through the same networks. I do not know whether the current coronavirus epidemic can still be stopped or mitigated so that it does not reach a critical level.

But however this particular event turns out, it raises deeply alarming questions.

In the 1990s the early ideologues of globalization suggested the world has entered a perennial ‘end of history’ scenario of abundance and connectivity. Almost nobody believes that in 2020, but that is the least of it.

Instead what we might be facing is that the whole epoch of globalization was an ephemeral blip, and its inevitability an illusion, about to be swept away by the more powerful forces of epidemics, climate change, resource scarcity and the political turbulence and violence they generate.

This is a possibility, not a certainty and even if things go that way, it should not be imagined in a binary fashion. It is tempting to connect various aspects of crisis situations into an overall ‘collapsitarian’ narrative and prophylactically fantasize about ‘collapse’ or ‘the event’, after which ‘it will be over’.

This is an emotional reaction of preventive despair, but in reality the global economy cannot just disappear overnight, as it has massive inertia, technology and vested interests backed up by state power on its side to keep it going.

It is possible, though by now difficult to see how, that the current epidemic will be brought under control before it infects say 10% of the global population and becomes endemic.

Similarly, by a massive interventionist turn (along the lines of a Green New Deal) to decarbonize the economic system and invest in carbon capture technologies and reforestation to sequester the CO2 already in the atmosphere global warming could still be slowed down, so it does not exceed 2C by 2100. For this yearly emission reductions of 5-10% would be needed, not a growth of emissions as it is happening currently.

Within a best case scenario of moderate warming, its effects could be mitigated by extensive urban planning (relocation), infrastructure (water) and health care investment, so they are not disproportionately concentrated in the geographic regions and social strata with the least resources. In this scenario a window of opportunity could still be open for new technologies to overcome resource constraints and globalization to continue apace on the way to a post-scarcity society. This passage is not completely barred, but, at the very least, seems a more and more unlikely best case scenario than a safe bet.

Suppose however that the best case scenario will not materialise and globalization, as we know it, is about to undergo some form of involution. The most immediate and disturbing question for those of us shaped and defined by this era is perhaps not even the usual ‘what do we do?’, but a more elementary one: if we cannot be citizens of the global village of eternal progress anymore, who are we going to be?

Notes

(a) GDP is a ‘flow’ measure: it’s a rate, not a stock, so this is not the cumulative amount of capital stock built up, but the level of economic activity per year. ↩

(b) Additionally, in 1871 most ‘economic’ activity in the world was still outside the monetary economy so the estimate for world GDP, the denominator in the ratio, might be an underestimation, although I think Maddison etc. tried to account for this. ↩

political-economy globalization climate-change complex-systems ecology epidemics covid19 growth