The COVID-19 crash and future scenarios

Last February-March I wrote a post on whether the shock of the pandemic could unravel the whole system of globalisation. From long-term estimates of economic growth I tried to show that the globalisation of the last 30-40 years was on a different scale than previous cycles of expansion of global trade and finance. Since this burst-like expansion of global trade and finance coincided with a similar growth of private and public debt, I speculated if the system could be more fragile than expected and might start to disintegrate as the pandemic hits it on a systemic level, not isolated to certain sectors or regions like in previous crises of the last decades. This disintegration has so far not happened. Before going into the reasons why, let’s look at the scale of economic fallout from the pandemic and how governments reacted in response.

Crash

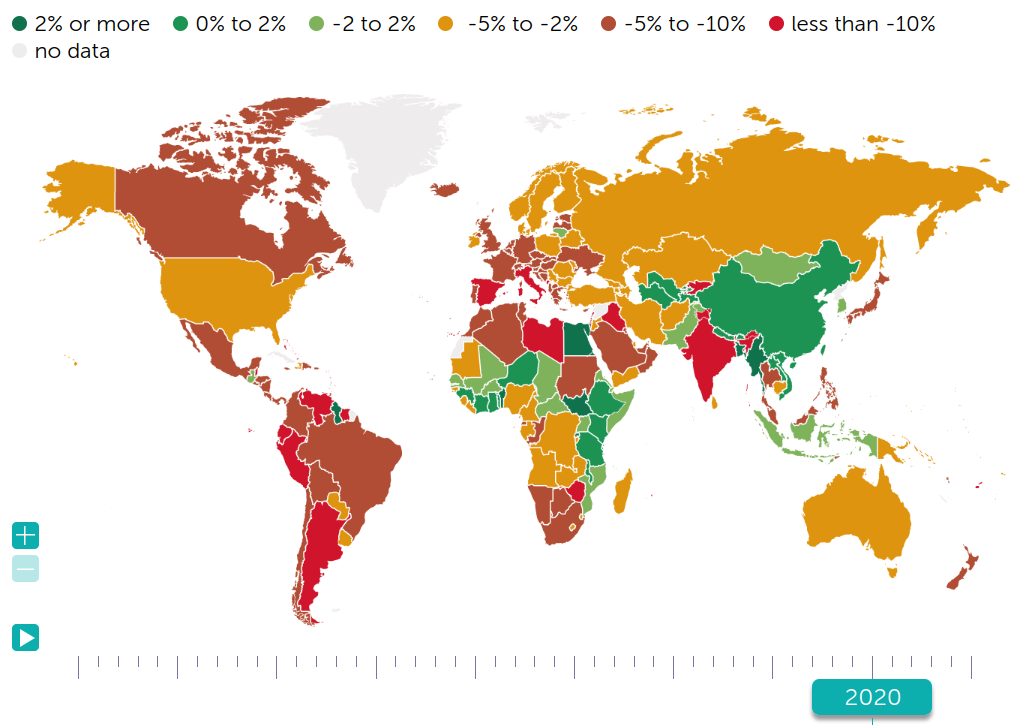

The world economy shrank by around 3.5% in 2020 while world trade fell by 9%.

This is slightly worse than in 2009 for GDP (-1.7%), but less severe for world trade which fell by

12% in 2009.

Whatever the exact numbers are, the headline figures for 2009 and 2020 are comparable.

Business as usual? In a sense it is still early days since a process of disintegration would take longer to work its way through the world economy. But for the moment a general de-globalisation does not seem to be happening, in fact some countries have already started increasing their trade again, most notably in East Asia, spearheaded by China.

The COVID-19 recession is very different from previous ones. A state-imposed demobilisation of the economic system occurred ranging from general shutdowns to milder non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). Output fell, in the first instance at least, because the state intentionally switched off certain sectors, like most of retail, tourism and hospitality.

The size of the recession varied depending on how long and severe the NPIs were, as well as on the size of countervailing government interventions and trend growth prior to the pandemic.

A few countries struggling with civil wars, government default and/or large-scale disasters experienced a collapse of economic activity (measured by GDP): Lybia (-67%), Lebanon (-25%) and Venezuela (-25%), followed by a few tourism-based mini-states.

The contraction was more than 10% for some Latin American countries (Peru, Argentina) and Spain that were hit hard by the pandemic and were fiscally constrained.

The fallout was around 10% for the worst hit European countries (UK, Italy, France) and India that applied harsh but belated lockdowns without stemming mass infections and therefore were locked into cycles of relaxing and re-introducing NPIs.

Japan, Germany, Brazil, the US, Australia/NZ and Eastern Europe saw recessions of around 5%. The reasons in this group of countries were diverse.

In the case of the US and to some extent Japan and Germany unconstrained fiscal intervention could be applied. In others trend growth had been higher (Brazil, Eastern Europe). Additionally, countries less reliant on services but having strong manufacturing exports (Germany, Japan, Eastern Europe) seem to have been less affected.

Many African countries had mild recessions or even modest growth (-2 to +2%), but the Maghreb countries as well as South Africa and its neighbours experienced a >5% contraction. China and Vietnam were two countries in 2020 that managed to suppress or prevent a mass outbreak [with the emergence of ‘Delta’, Vietnam has been struggling with mass infections and death since the summer of 2021] and sustained a +2% expansion which is still approximately 5% under their trend growth.

To summarise, the contraction of GDP was the most severe in Europe, Latin America and India, while in East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa the contraction was either smaller or there was even moderate growth.

[source: IMF datamapper]

[source: IMF datamapper]

Response

To make up for the fall in spending and the income loss of employees rich states took over much of the private sector wage bill, while almost all states implemented various measures increasing benefits, sending one-time down-payments to households or providing emergency loans and loan guarantees for businesses.

The size of stimulus measures in 2020 was significantly bigger than in 2009. The exact numbers will depend on what is defined as part of the ‘stimulus’ on top of baseline spending, so absolute values are sensitive to methods.

Looking at numbers relative to 2009, according to the definition used by McKinsey the size of the measures as a percentage of GDP increased 10-fold from 2009 to 2020 in Western European countries, Japan, Brazil and India, and around 3-5 fold for Canada and the USA.

According to the IMF’s breakdown of stimulus measures by type, much of them were loans, loan guarantees and equity support and not direct spending. Nevertheless the spending increase itself was also about 12% of GDP in advanced economies (using the IMF’s definition). There is a big difference with emerging/middle income economies (EMMIE) where this figure was around 4% of GDP and low income countries where it was 1.5% on average.

Liquidity support was on average at the same level for advanced economies as additional spending, but in some countries such as Germany, Japan and Italy it was even higher, more then 30% of GDP, whereas in EMMIEs and low income countries liquidity support was smaller than the increase in spending.

It was at the cost of this unprecedented fiscal and monetary intervention that the state-ordered demobilisation of the economy did not lead to a collapse of national income.

By definition this means that government debt grew, reaching 100% of GDP globally, 10% above the projections made in 2019.

Fiscal intervention was one aspect of government interventions, but there was another one: monetary stimulus by central banks. Once again the money supply was significantly expanded, led by the Fed, but also the BoE, the ECB and the BoJ.

One major difference from 2009 was that whereas then the largest stimulus was applied by China, which included both direct spending and (even more) expansion of credit to industry via its state-controlled banking sector, this time China implemented a (proportionally) smaller stimulus program than Europe and the US. This is mainly because lockdowns in China were much shorter and because of an early recovery no ‘furlough’-type programs of general wage support had to be applied.

Pandemic prospects

Vaccination programs are currently [Summer 2021] going ahead in Europe and North America and projected to cover most adults by the 4th quarter of 2021 in many Western European countries and some wealthy countries started to vaccinate adolescents as well.

The countries which managed to prevent or suppress outbreaks (in East Asia, Australia/NZ) were under less pressure to act quickly but also started their vaccination roll-outs while keeping their borders shut.

Poor countries have much less access to vaccines so far, with Africa around a 2% vaccination rate by July 2021, Latin America around 40% and Asia around 30%.

Seroprevalence studies from urban areas of India, Pakistan and South Africa showed typically 20% to 50% of the adult population in cities already infected in early 2021, forming a level of population immunity, which is however not enough for the epidemic to end because of the more contagious variants (mainly ‘delta’) that appeared in 2021. Consequently, large outbreaks re-appeared from the spring of 2021, and are currently continuing through the summer. In late July 2021 some of these outbreaks, for instance in India and North Africa, are now [summer of 2021] again shrinking that could be a sign of population immunity.

Immune escape by new variants could undermine these calculations, but vaccines are likely to provide good protection at least against severe disease, and the timescale of adapting vaccines to new strains will likely become much shorter too.

A global coordination to eliminate COVID-19 by simultaneous lockdowns and travel bans seems unlikely both for political and technical reasons and given the contagiousness of Delta it is practically impossible to do.

The likeliest scenario then is vaccination providing protection for most of the population in high income countries, meanwhile in lower income countries higher population immunity due to infections, a multi-year vaccine roll-out and the much lower median age will keep the disease burden at a lower, but not negligible level.

Whether the disease burden has been in fact lower in low income countries so far is not clear as no reliable mortality statistics are available from many LICs, but excess death (per population) estimates for South Africa are higher than for most of Europe and in Egypt comparable.

In Manaus, Brazil, the closest thing we have to an unmitigated epidemic on a large-scale, excess death estimates suggest 0.4% of the total population might have died and this was before the renewed outbreak from the summer of 2021.

Excess mortality analysis suggests a similar level of mortality burden for the most heavily hit Latin American and East European/post-Soviet states with 3-6 COVID-19 deaths per 1000 population.

With the appearance of the delta variant which is about 3 times more contagious than the original strain, countries that had previously successfully implemented a suppression and border closure policy, such as Taiwan, Vietnam, Thailand and China are in the summer of 2021 also seeing large outbreaks.

With the exception of China where more than half of the population are already vaccinated these countries have low (<35% on the 1st of August) levels of vaccination. This means that they might experience levels of infections and therefore hospitalisations and deaths comparable to Europe/US in the Spring of 2020 and Winter of 2020-21. The low speed of vaccination in some East Asian countries raises questions about the narrative that their success in preventing mass outbreaks until the summer of 2021 was explicable by a more effective state and/or a more rule-abiding population. If slow vaccination rates are due to low demand, ie. vaccine hesitancy then the argument about state capacities could still stand, but it would still be inconsistent with culturalist explanations of law-abiding and/or collectivist attitudes.

In any case with the delta variant’s contagiousness on the one hand and vaccination programs on the other it is likely that most societies will reach a level of population immunity towards the end of 2021 so that sudden and large new outbreaks become less likely. Instead there would be a lower level of endemic transmission, modulated by seasonality, births and waning immunity. This could lead to SARS-CoV-2 adding a disease burden similar to one (or a few?) influenza season during the winter months.

Assuming that vaccine programs and population immunity will keep the disease burden at a level below where governments would re-introduce strong NPIs, the economic recovery that started in most countries in the second half of 2020 or early 2021 is likely to continue through 2021.

Recovery

Most larger economies have now positive growth rates and it seems there will be a strong recovery of GDP figures in 2021. In the United States the large fiscal and monetary stimulus is estimated to result in GDP not only recovering from the recession but even slightly exceeding the pre-pandemic GDP trend line. There is talk of inflationary pressures and shortages causing supply chain disruptions that are after-effects of the sudden shocks during the pandemic. Will these wear off or might they interact in a way to amplify each other and disrupt the recovery? Nobody knows for certain as economic models do not seem to be able to make reliable forecasts due to the complexity of the problem: both data and model structure are incomplete to make predictions with high confidence. The default forecast for the moment however is a recovery for this year and growth continuing in 2022.

Several things might derail this. First, there has been a massive buildup of corporate debt even before the pandemic since the 2009 recession.

During the pandemic a lot of businesses were kept on a government lifeline, in many cases meaning loans. Since ‘re-opening’ is unlikely to be a complete return to normality for industries like travel and hospitality, it is an open question if there will not be a chain of bankruptcies in 2021-22, which could start a new private debt crisis, perhaps this time starting from corporate debt, rather than housing and collateralised household (mortgage) debt as in the great financial crisis (GFC) starting from 2008.

During the pandemic a lot of businesses were kept on a government lifeline, in many cases meaning loans. Since ‘re-opening’ is unlikely to be a complete return to normality for industries like travel and hospitality, it is an open question if there will not be a chain of bankruptcies in 2021-22, which could start a new private debt crisis, perhaps this time starting from corporate debt, rather than housing and collateralised household (mortgage) debt as in the great financial crisis (GFC) starting from 2008.

Another potential time-bomb could be the Eurozone, similarly to the 2010s following the first phase of the financial crisis: Greek government debt to GDP was ‘only’ around 110% in 2008 (then jumping to ~140% by 2010, and ~170% by the mid-2010s following austerity measures shrinking output further), but now it is 206%.

There has been a similar increase of public debt for Italy and Spain and indeed almost all EU countries. The difference is that this time, finally, the EU took a step towards the mutualisation of debt so that recovery programs should be to some extent funded jointly. This makes a run on Greek (etc) debt less likely, but does it make it impossible? The recovery program does not seem to be big enough (~300 billion euros in direct spending over a 7-year period, that is around 0.3% of the EU’s annual GDP) to generate much growth on its own and much of Southern Europe seemed stagnant already before the pandemic. Tourism is still to a large extent shut down and unlikely to completely recover this year. Where will growth come from in Southern Europe and if it does not, will these countries not face revenue problems that could cascade into a new sovereign debt crisis? If this will not happen and yields stay as low as they are and therefore interest payments manageable on Southern European government debt, this would support the view that the Eurozone debt crisis of the 2010s was avoidable and self-imposed by the inept and dogmatic policies of the EC/Eurogroup/ECB.

It is unclear if the European Commission (or whoever calls the shots on economic policies in the EU) have changed its views on what makes a recovery sustainable and would be willing to extend stimulus if growth rates slump or if it would switch back to austerity policies as in the early 2010s.

The UK might also experience a further shock if full custom controls with the EU are finally switched on: these were put off to October 2021 and some until January 2022. Disruption to trade with the EU have so far not been that significant (ie. seem to be recovering to the pre-2020 trend line), but this might change when full customs checks start to be applied. Nevertheless the effect so far looks more like a moderate drag on growth rather than a shock that could push the UK into recession. As long as there is ‘faith’ in the sterling and the government can borrow cheaply, the UK does not look like a domino likely to fall, thought its growth rate might no longer exceed that of the Eurozone as it mostly did in the period 2000-2016.

An interesting question is why China was more cautious in its stimulus spending now compared to the GFC. Was it simply because it did not need to do more for its economy to rebound because of the rapid suppression of COVID-19 and its economy less dependent on exports? Or is there something more to this? If so, that ‘something’ could be (undisclosed) problems in the Chinese banking sector that makes the government not wanting to put more strain on it by forcing banks to up the credit supply.

Finally, there has been a large outflow of funds from ‘emerging markets’, much more so than in the first 1-2 years of the GFC. While lower and middle income countries have run up government deficits much less than high income ones, their debt levels still increased, typically in the range of 5-10%, because of lost revenue and (modestly) increased spending. Medium-sized countries like Turkey, Brazil, Argentina, Mexico or Indonesia with a history of sovereign debt crises saw their debt levels rise and it is a question if the currency or the banking sector might snap in some of them if capital flows do not return to their pre-pandemic level and there is too much debt that cannot be rolled over or interest rates on debt spike.

What about globalisation?

Whether the recovery will be sustained for at least the coming 1-2 years or not, in retrospect I feel there were more fundamental problems with my arguments on the fragility of globalisation.

The structure of the argument was the following. Globalisation on the current scale is rather recent: it mostly happened since the second world war and especially in the last 40-50 years - more a sudden explosion than gradual growth over centuries.

Although there had been some degree of globalisation ever since the sixteenth century and by some measures even before, for millennia, the cumulative growth of the last seventy years in terms of volumes of traded goods/services and of global economic output and energy use is (much) larger than what had occurred between the first civilisations and 1945.

In the last forty years of explosive growth of international financial and trade flows there has also been a secular growth of all forms of debt, especially in the wealthy countries: corporate, household and public debt rose to levels several times of annual output. The two long business cycles (1992-2000, 2001-2007) before the GFC have been notoriously debt-driven, especially in the United States and Europe (Southern Europe, the UK, Ireland…), but also parts of Asia and Latin America.

The 1992-2000 cycle was marked by a debt-fueled stock market bubble (dotcom bubble) and the 2001-2007 cycle by unprecedented housing bubbles and debt-financed household consumption. Employment growth for the more recent business cycles was weaker, and the same goes for output growth, with the long business cycle following the GFC (2009-2020) the weakest of all by both metrics.

In short, what I argued was that 1) global trade networks expanded so fast that supply chains have become too stretched and many economies too dependent on trade, while 2) all sources of demand (consumer, business and government spending) are too reliant on debt. 3) When the system is hit by simultaneous shutdowns of much of the global economy it might not have enough resilience to withstand this and there could be an implosion in globalisation unlike anything since its emergence.

While there was a roughly 5-10% contraction in output and trade in 2020, it was comparable to that of 2009 and following government interventions there has been a strong rebound.

There are currently shortages in some goods (eg. computer chips) but overall supply chains of multinational companies could manage the shock of lockdowns: a 10% reduction in economic activity is not a collapse, and in fact it was mainly services, not manufacturing that was shut down. The idea that the shock was too ‘systemic’, so corporations will not be able to cope was therefore somewhat of a ‘handwavy’ argument. In reality they could manage it, at least with the help of governments. It is true that without government loans/grants/subsidies there might have been a real collapse, but government intervention to keep the economic system ticking was essential in the GFC (and before) already. Overall, the system was robust enough to withstand the storm.

The debt hangover from government interventions might still be a problem, either in the form of unviable businesses not being able to pay back loans or sovereign debt crises. If that happens, we could say the problem was just put off but not solved and the global economic system was too fragile and debt-ridden.

The world economy can arguably be described as ‘unstable’ in the sense that there is a strong interdependence across markets and a mountain of debt in the system, so there can and will be periodic debt crises that spread rapidly. But this does not mean the system is close to a tipping point where it might collapse, if by collapse we mean a fall in activity of at least 30-50%. While some Marxist economist claim profitability is at a record low currently, nominal corporate profit figures seem to be recovering (Q1-Q2 2021). Even with more ‘zombie companies’ around, the recovery should go ahead at least in the short term.

But in a more general sense I think the line of argument was faulty: the fact that globalisation arose very rapidly and that a lot of debt has been built up since the 1980s does not imply it is an inherently fragile system and might collapse when hit by a large shock like the pandemic. First of all, complex systems often emerge in a burst, after a much longer period of slower growth. The institutional, legal and cultural basis for global trade had been there for a much longer time, and it was new information technology, regulatory frameworks for trade, finance and investment and cheaper shipping and travel that made the explosion after the second world war and again from the 1980s possible. But burst-like growth does not mean a system is out of control and headed for collapse: a sigmoidal curve has a first part that looks exponential but then it saturates.

That is for the macroeconomics in the short term. But what about climate change and the need for an energy transition? Could this be the ‘systemic’ crisis that tears down globalisation?

This question invites trying to make predictions about the climate, the world economy and politics at the same time - the complexity is so high it is doubtful even qualitative predictions are possible. I will still try to make some, while emphasising the following are just speculations, where I’ll only list the ‘branches’ that seem to me the most likely, although obviously there are many other possible futures.

It is unlikely the response to the climate crisis will be fast enough since the crisis is already ongoing. Targets for decarbonisation have been recently set by the major economies, with China setting a target of emissions peaking by 2025-2030 and reductions only afterwards. The announced targets set out timelines of emission reductions that fall short by one or two decades to avert >2C warming. Burning coal, probably the worst form of fossil fuel consumption, will still be going up for at least several years (around 5%/year currently), though for net zero emissions a yearly reduction of around 5% would be needed.

So the most likely scenario would be the climate crisis getting worse: more extreme weather events, summer heat waves and forest fires. But these changes are likely to be woven into the fabric of a globalised capitalist economy instead of totally disrupting it: mitigating the climate crisis will create various new industries and new forms of population control.

The pandemic might be a dressing rehearsal in this sense as well: the precedent is now set for the state to drastically intervene and close down cities or even countries and ramp up surveillance. In the climate crisis, moving populations and forms of migration control will likely become part of the normal functioning of the state. The climate emergency, higher fuel costs and more home-working might result in somewhat less travel and perhaps more regionalisation of the world economy. Travel and migration for highly qualified professionals and of course for the rich are unlikely to be controlled or significantly reduced.

More broadly, cultural globalisation based on near-universal internet and smartphone use will likely continue, along with the spread of English. The secular decline in political participation (turnout at elections, party and union membership) will also likely go on, further hollowing out Western liberal democracies. Liberal-democratic states will likely become more and more technocratic and regulatory apparatus run by professionals from elite universities with the general population caring less about such things while an apolitical, individualistic and hedonistic consumer attitude focused on instantaneous gratification - hot-takes and takedowns - becomes ever more deeply entrenched.

This does not mean there will not be flare-ups of potentially violent forms of political protest, but these will likely be short-lived single-issue protest movements along the ‘Gilets Jaunes’ model: ideologically heterogeneous and confused, operating by memes and generally anti-political (‘they are all bastards’ etc) without creating organisational structures - and therefore likely to be short-lived. Right-wing populist governments might still be elected and cause some turbulence, but Europe’s far-right seem to be ‘normalising’, accepting euro-realism (EU and Eurozone membership with its budgetary rules and elite secrecy), so such governments might be distinguishable mainly by their immigration policies being somewhat more cruel. Social inequality and related discontent will likely be addressed by progressive technocrats of the Elizabeth Warren type in the very best case.

In countries where political pluralism has only weak roots in society there will likely be a move towards ‘managed democracies’ along the lines of Russia or Hungary, with a hegemonic government party using broadcast and social media as well as high-tech surveillance to keep opposition groups marginal enough so that open repression is only occasionally needed.

While some of these ruling elites might fall, it is unlikely this will lead to a general upsurge of political participation, instead they will be replaced by another oligarchic group that takes hold of the state and the adjoined rent-seeking apparatus as a revenue stream.

Consent will be bought by the state via providing some level of stability and support for the least well-off outside the metropolitan centres along with culture wars against the ‘woke’ West and metropolitan liberals, while those within the city gates are allowed to either pursue a lifestyle of Westernised consumption or emigrate.

In the global South climate change might be truly catastrophic because of the effects of rising temperatures on both human health and agriculture. This will increase migratory pressure on the West and in the intermediate zones especially around Europe (North Africa, the Sahel and the Middle East). Repressive states in this buffer zone will likely get more funding from the West in exchange for holding back migrants by force.

Overall, I would expect global trade and information technologies to survive under conditions of the climate crisis too. Travel and migration for elites and professionals will probably be secured, but might be more curtailed for others. In this respect the travel bans and other restrictions of the pandemic could prove to be templates.

political-economy globalization climate-change complex-systems epidemics covid19 growth